24 February – 05 May 2024

THE LIMITS TO GROWTH Chapter 1

THE DESIRE FOR A DONUT(ECONOMY)

— A group exhibition on degrowth, the donut economy, and the possibilities of well-being within planetary boundaries.

Participating artists: bambi van balen & Branco van Gelder | TOOLS FOR ACTION, Eline Benjaminsen & Dayna Casey, Cian Dayrit, DISNOVATION.ORG, Rosie Heinrich, Toril Johannessen, Carlijn Kingma, Jonas Staal, Marjet Zwaans & David Habets

The exhibition THE DESIRE FOR A DONUT(ECONOMY) functions as a conversation starter for the year program THE LIMITS TO GROWTH, which intends to reset the relationship between economy and ecology. With the work of twelve artists, the exhibition explores the possibilities of grounding a system in which economic and ecological well-being are considered integrally, within planetary boundaries. What shape should such a more-than-human and climate-inclusive economy that promotes a broader definition of welfare take?

The current capitalist system based on the promise of increasing economic growth, progress and prosperity generates a permanent state of crises. The accumulation of the various crises we are experiencing today—from climate and health crises, to economic, social and political crises—are the result of an all-encompassing exploitation of the environment, human and non-human alike. The exhibition THE DESIRE FOR A DONUT(ECONOMY) presents the work of a group of artists providing insight into the systemic crises we are facing. In response to this systemic crisis, their work focuses on the democratisation of current economic systems and features proposals for more hopeful, egalitarian and reciprocal economic systems, informed by alternative economic systems such as the donut economy, eco-socialism and the degrowth movement. The participating artists share the realisation that such a complex, multi-layered and dynamic system requires more than one all-encompassing solution, and are united by a seemingly simple thought: infinite growth on a finite planet is simply not possible. To that end, the exhibition invites you to think about what really matters: decolonising growth as a profit motif, countering inequality, liberating creativity, and strengthening solidarity.

DONUT ECONOMY

As early as 1972, The Limits to Growth, the first report by the Club of Rome, concluded that it was impossible to ensure the exponential growth of both the economy and the world population on the basis of the limited and finite availability of natural resources. Through a number of future scenarios, the report showed that attempts at unbridled growth would sooner or later—but rather sooner—end with the collapse of socio-economic and ecological systems. Fifty years later, limits and borders are back on the political agenda, borders to “protect” the known level of prosperity of the Global North from incoming migrants. Yet, now it is not only national borders that are “threatened”, but also planetary borders which are threatened by climate change.

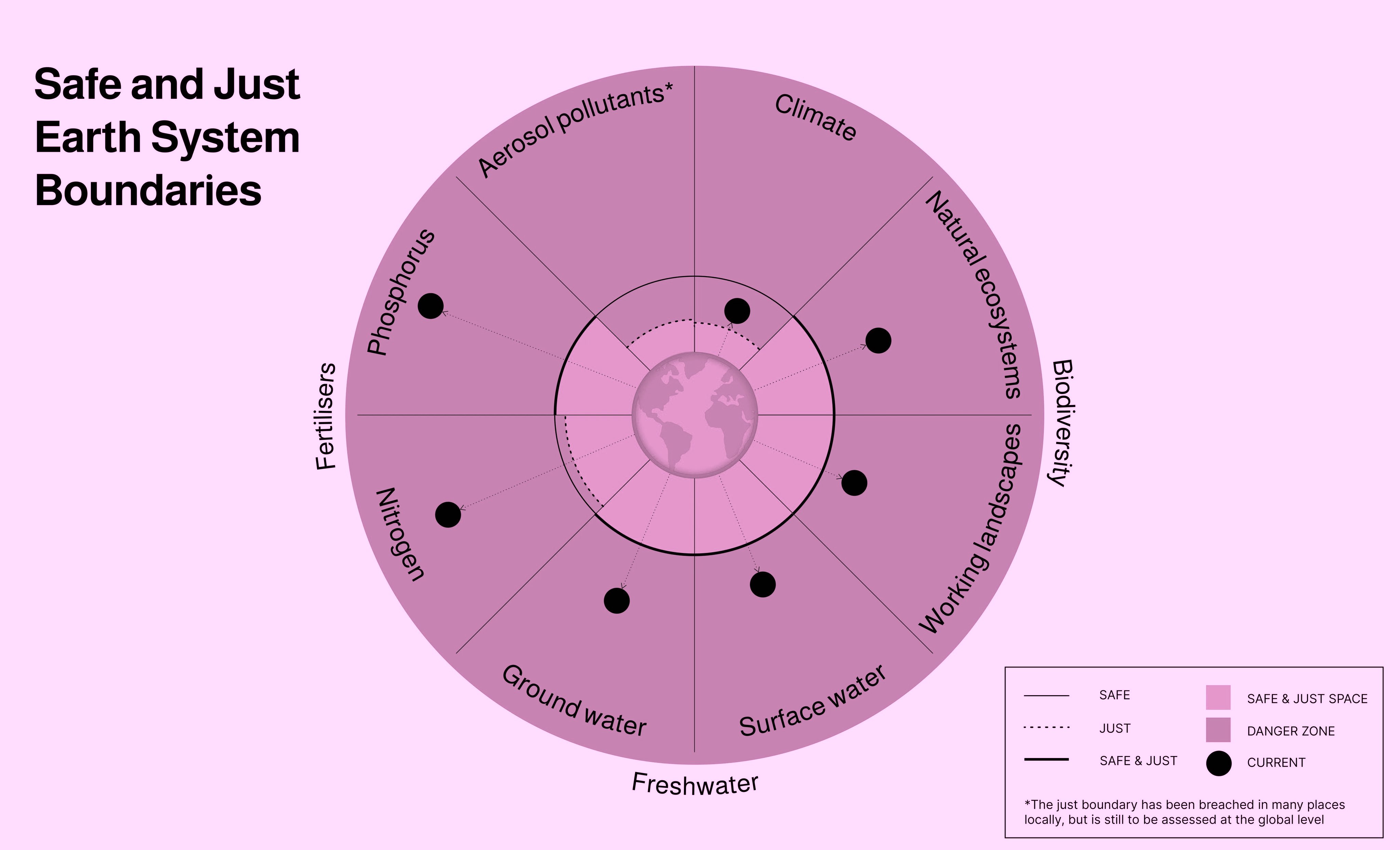

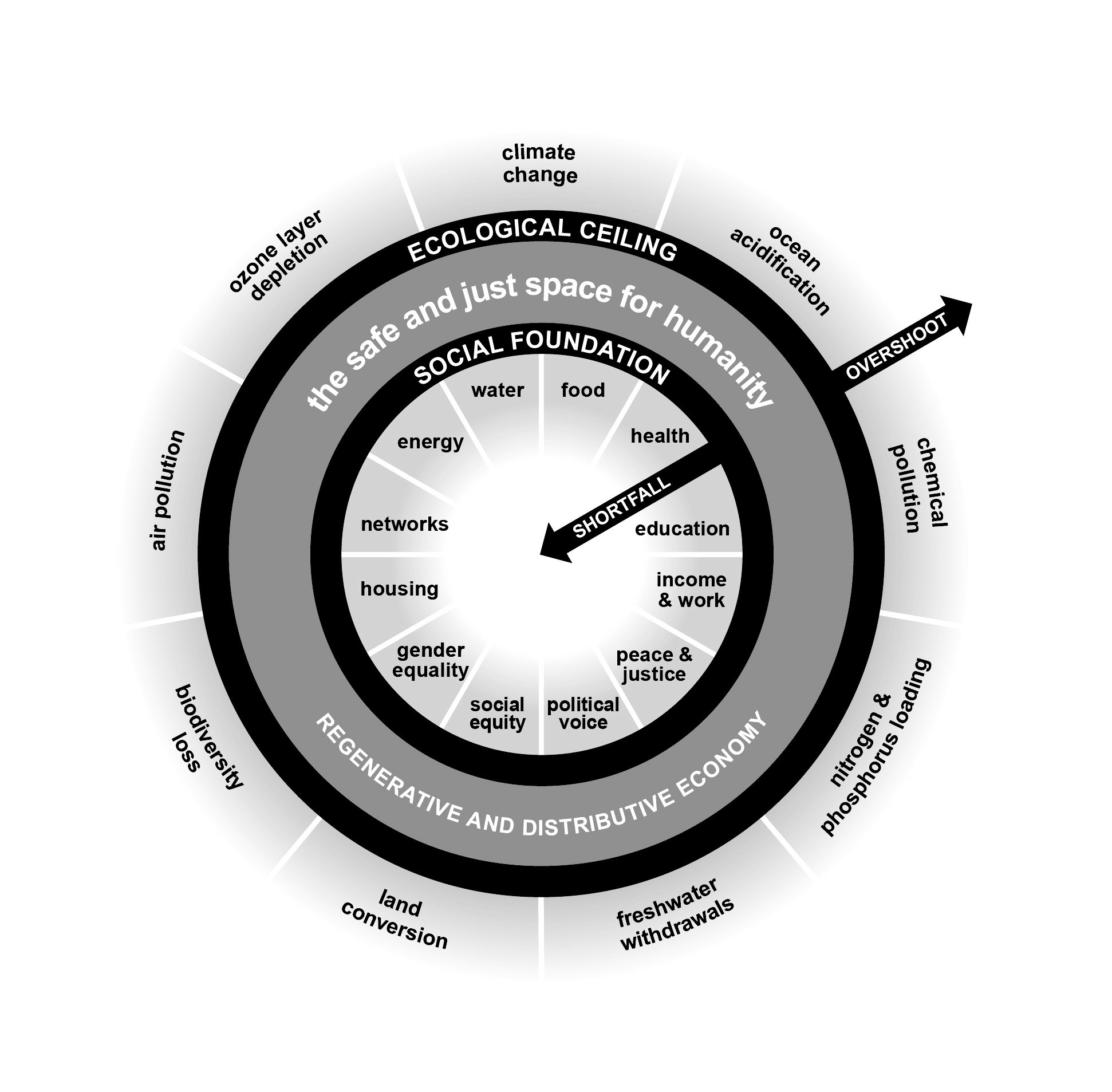

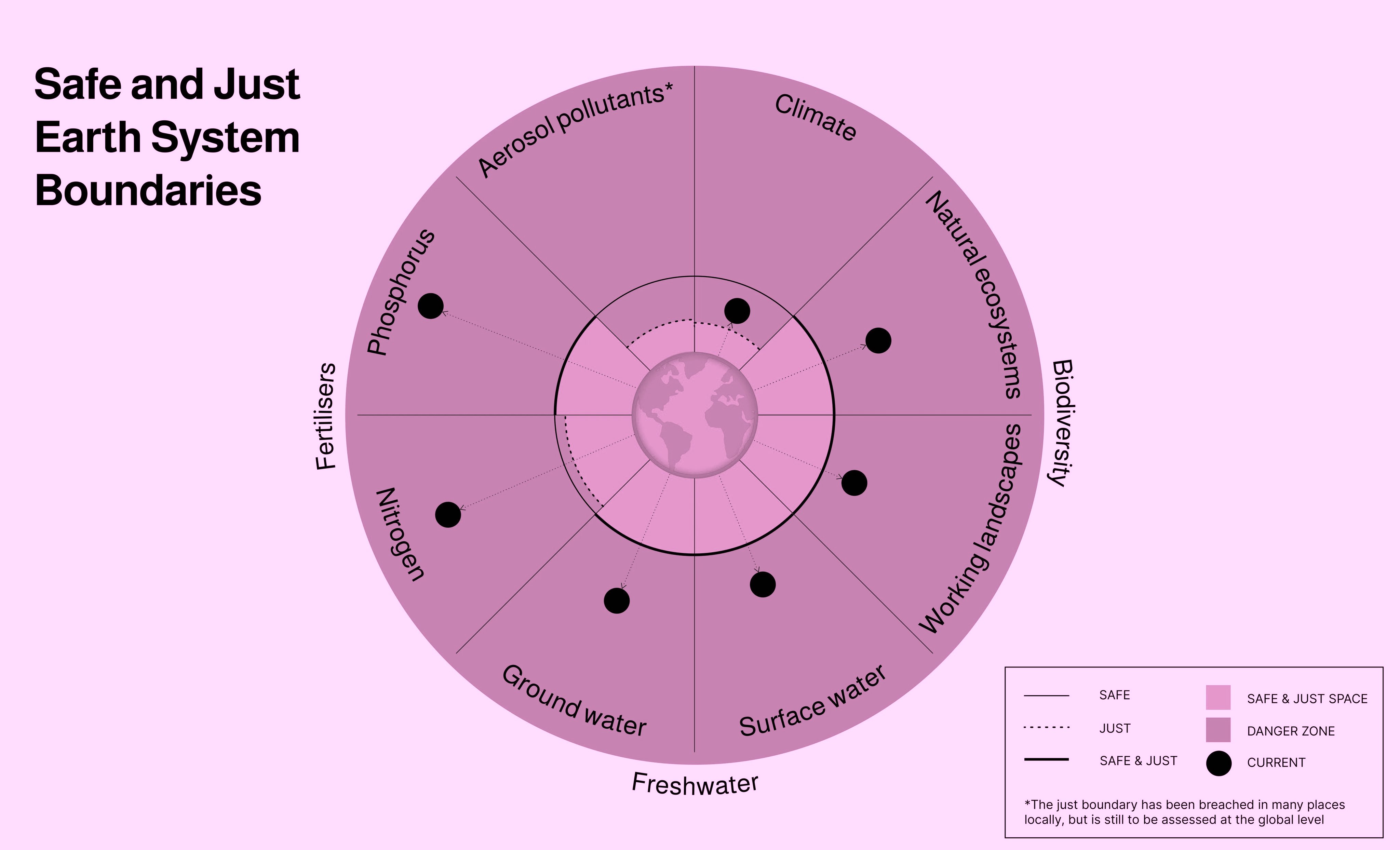

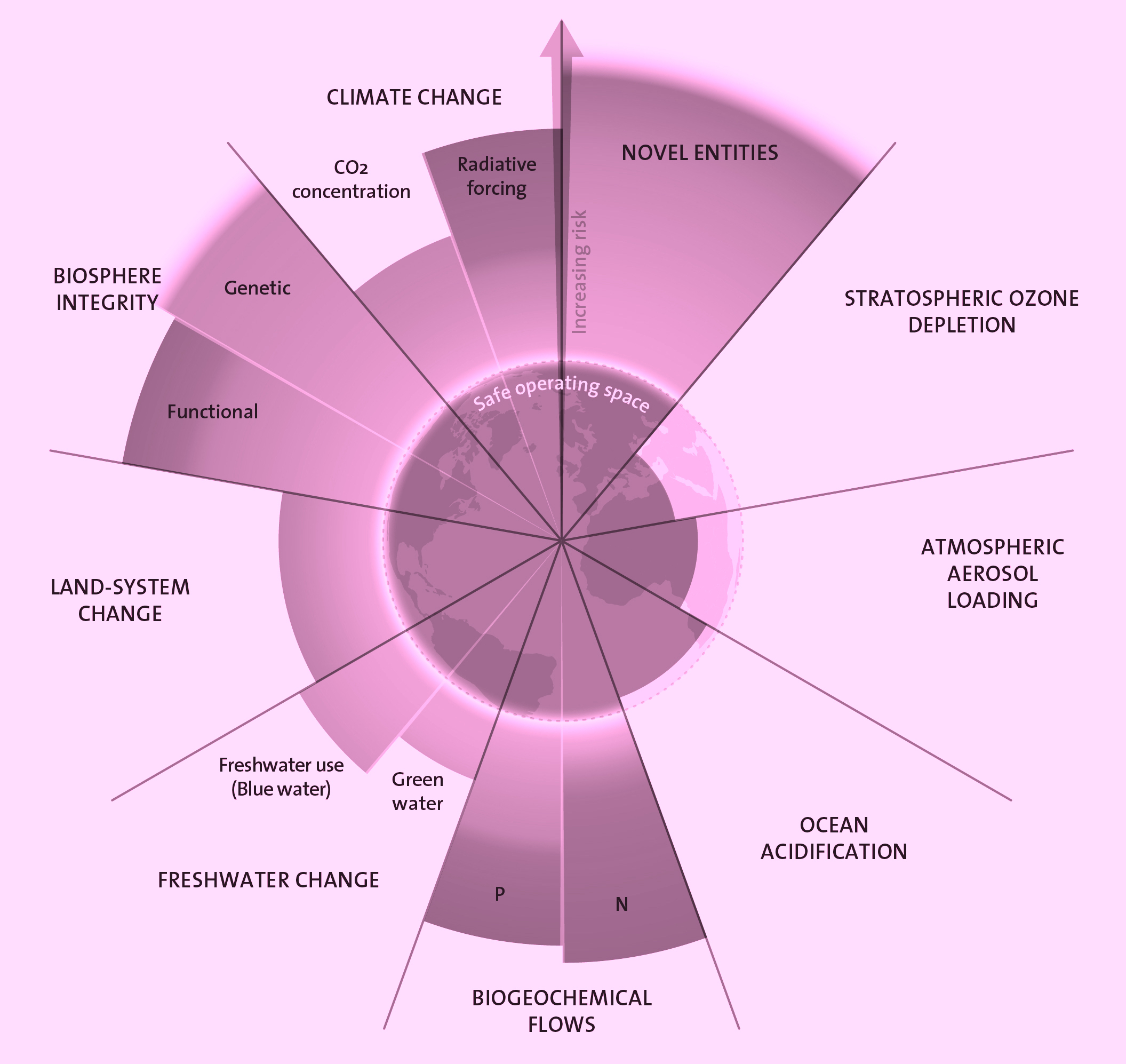

How do we get to the point where we can meet everyone's needs without sacrificing the planet? This question is at the heart of economist Kate Raworth's 2017 book Donut Economics. Raworth argues that we need to start looking at the economy in a fundamentally different way and let go of our fixation on growth. The addiction of a small influential elite to economic growth has led to extreme inequality and unprecedented (ecological) degradation of the Earth. With her donut economics, Raworth argues for a broader view that includes both human and planetary well-being. She does this through an economic system in which basic human needs are met within a society that allows for development, while at the same time not overstepping planetary boundaries. At the core of the inner circle of the donut—the social foundation—human misery, calamity and disaster, including hunger, illiteracy and social inequality are situated. On the outside of the outer ring—the ecological ceiling—we find the degradation of the planet, as caused, among other key factors, by climate change and biodiversity loss. Between these two circles is the donut: the space in which, within the limits of the Earth, we can meet the needs of humans and non-humans alike. To promote human and ecosystem well-being, finding the right balance is thus essential. The donut, Raworth concludes, “represents a social foundation of well-being below which no one should sink, and an ecological ceiling (...) that should not be surpassed”.

Unfortunately, the so-called safe and just operating space within which humanity can operate, as described in Raworth's donut economics, has already been overstepped in most places. Six of the nine planetary limits—global warming, precipitation and drinking water (water scarcity), ozone depletion, air pollution, ocean acidification, nitrogen and phosphorus (disruption of biochemical cycles), chemical environmental pollution, deforestation, loss of biodiversity—have been exceeded in 2023. The economy still does not seem to be able to effectively decouple itself from the excessive consumption of non-renewable resources and the pollution and emissions that come with it. The opposite often turns out to be true: the market-based money system strongly favours economic growth, pushing for additional loans, lowering environmental and climate standards (note the effective lobbying by the fossil industry at United Nations Climate Conferences), and implementing longer working hours, higher retirement ages and cuts in social security in order to maintain the known level of growth, normalized as part of the fossil economy.

The economy still does not seem to be able to effectively decouple itself from the excessive consumption of non-renewable resources and the pollution and emissions that come with it. The opposite often turns out to be true: the market-based money system strongly favours economic growth, pushing for additional loans, lowering environmental and climate standards (note the effective lobbying by the fossil industry at United Nations Climate Conferences), and implementing longer working hours, higher retirement ages and cuts in social security in order to maintain the known level of growth, normalized as part of the fossil economy.

DEGROWTH

Whereas the donut economy model provides a useful alternative to the seemingly all-encompassing workings of advanced capitalism, and as an overarching system provides adequate space to think about the relationships between economy and ecology, between people and planet, it is equally important to look at more local and situated forms of non-exploitative economies. In other words, we need to believe that there are alternatives at hand if we are to counter and resist a system of capitalist oppression and exploitation.

Such a non-exploitative relationship is evident in the degrowth movement. The concept of degrowth first manifested itself in the 1970s and came to maturity in the early 2000s in France. It is important to stress that the concept of degrowth does not imply recession or negative growth, and should not be interpreted literally in that respect. Degrowth involves phasing out certain forms of non- or less necessary forms of production in order to reconnect and balance economy and ecology. Degrowth of specific forms of production takes place in a planned and democratic manner and affects only the richest, wealthiest group of humans and the products they consume and use. These include luxury goods such as SUVs, meat and private jets. Thus, degrowth is completely different from the sudden and disruptive recessions we know. Recessions almost always come at the expense of the poorest and most vulnerable people in society. They lose their jobs or are forced to spend more on their daily shopping. Degrowth, on the contrary, suggests that the poorest groups in society are allowed to thrive whilst the richest give up proportionally. Cutting back on the production of luxury goods leaves additional means, labour and natural resources to produce essential goods and services needed by the poorest and most vulnerable, such as proper education and healthcare.

Similar to donut economics, degrowth addresses social and ecological indicators in their context, by seeking alliances and connecting existing practices and methods. These include universal basic income, cooperatives, resistance, protest and civil disobedience, as well as the commons. Degrowth is a process of political, ecological and social transformation that reduces a society's output and improves its quality of life, focusing on existing concerns and needs, by cutting down on consumption and setting up shorter production chains.

At the same time, degrowth is an invitation to retrospectively reflect on history: how did Western “civilisation” create such a destructive and production-oriented system, which simultaneously deteriorates the living environment and exploits people? Within this system, genocide and ecocide are two sides of the same medal, manifested in the ongoing struggle for land sovereignty by oppressed groups against governments and corporations seeking to capitalise on land conversion, for oil extraction or logging, for example. This reflection requires us to learn from these oppressed populations from the past (and present) and the Global Aouth, where degrowth is about overcoming Western colonialism, for the sake of respecting, caring for and recreating universal rights and diversity in a globalised world.

If, through resistance, we manage to free ourselves from such totalising economic (and equally patriarchic) conceptions, we can begin to build new worlds on equal and reciprocal principles, including ecofeminism, self-determination and organisation, the commons, openness and freedom of movement. In other words, how can we live well without transferring costs and attributing debts to others, the planet and future generations, as the basic principle for climate justice? Within this, what are our basic needs and how can we fulfill these in a sustainable manner? Is there such a thing as frugal abundance? Cultural changes opposing a totalising capitalist system, moving towards principles of degrowth and the donut economy are not impossible. All across the world we see (local) initiatives inventing and implementing ways of living, based on reciprocity, care and sustainability. Initiatives that create new horizons beyond profit maximisation as the ultimate objective, incorporating a broader definition of well-being and well-fare.

“We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art, and very often in our art, the art of words.” ― Ursula K. Le Guin

Curated by Niekolaas Johannes Lekkerkerk, assisted by Sergi Pera Rusca.

THE DESIRE FOR A DONUT(ECONOMY) has been made possible with the support of the Mondriaan Fund, Municipality of Delft, Gieskes-Strijbis Fonds, Het Cultuurfonds, Stichting Zabawas, Van der Mandele Stichting, Stichting Mr. August Fentener van Vlissingen Fonds, OCA – Office for Contemporary Art Norway. We thank them all kindly for their support!